Cyprus: A Journey Through Colonialism, Conflict, and the Quest for Unity

The island of Cyprus, located in the Eastern Mediterranean, also known as the Birthplace of the mythical goddess Aphrodite, praised for its flourishing natural resources, and ancient archaeological sites, has a complex and divided social history that is often forgotten. The island’s communities, shaped by both historical ties and more recent geopolitical events, find themselves divided not only by land but by differing identities, memories, and aspirations. What are the origins of the current communal tensions in Cyprus, and why are they persisting? Understanding why Cyprus is divided requires a look into its historical context, the events leading up to the split, and the ongoing impact on both communities.

Cyprus divided itself into two main groups, and it all began when the Mycenaean Greeks colonized the island around 3500 years ago. Cyprus would then be held by many great powers over thousands of years like Assyrians, Egyptians, Persians, Romans, Ottomans, The British Empire… The reasons why so many different nations wanted to conquer Cyprus was because of its special attraction due to its strategic location, located in the eastern Mediterranean Sea. This large number of different cultures all having its history on Cyprus’s territories has an impact on the struggle to label Cyprus as part of one specific country. Cyprus is a mosaic of all it’s been through.

The Ottoman Presence

In 1571, The Ottoman Empire, later known as the Turkish empire, stormed the island of Cyprus and took it over. That began a period of Turkish migration to the island, as well as the cultural conversion of some Greeks. During this period, the island’s population was primarily composed of Greek Orthodox Christians and a minority of Muslims. Under the Ottoman rule, Cyprus’s economy was failing. The Ottoman administration allowed a degree of religious autonomy, but tensions between the communities simmered beneath the surface. This led to movements of rebellion, which enabled resentment against the power to grow, and eventually movements of independence broke out. Greek Cypriots revolted against the colonial administration demanding union with Greece. The Ottoman’s response to these rebellions was “lending” the island to the British Empire in 1878. The Ottomans still technically owned the island but allowed the British to rule it in exchange for support against the Russians, as there was the Russo- Turkish War (1877-1878) happening. Britain officially annexed Cyprus in 1914 in response to Turkey’s alliance with Germany during World War I. The British Rule period was marked by significant changes in the island’s political, economic, and social structures. The British administration introduced modern infrastructure, including roads, railways, and telecommunication systems, which facilitated economic growth and development. But colonial rule comes with its glaring impediments. The colonial administration implemented policies that often favoured one community over the other, emphasizing existing tensions between Greek and Turkish Cypriots. For example, the British used a divide-and-rule strategy, which involved manipulating ethnic divisions to maintain control over the island.

Self Determination and Rebellion

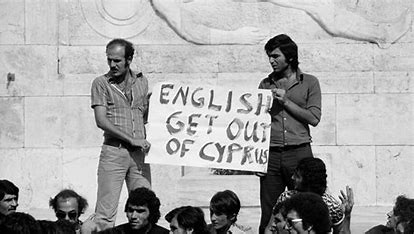

But it wasn’t until the 1950’s that intercommunal tensions really started to rise. By the end of World War II, the views of the two main communities clashed in what they saw for the future of the island, as the rest of the world was in a decolonising trend. The Greek Cypriots, led by Archbishop of Cyprus – Makarios III, saw themselves as Greeks happening to live on an island close by. They still felt connected to Greece as it was what they considered the motherland. That’s why unionists, people who sought for union with Greece, favoured the concept of “enosis”, form ancient Greek “ἕνωσις” (hénōsis), meaning “unification” or “union”. This aspiration was led by the National Organization of Cypriot Fighters (EOKA), whose campaign aimed to end colonial rule and had launched an armed struggle against British rule. It launched its campaign on 1 April 1955 with a series of bombing attacks against government offices in the island’s capital Nicosia. No one was killed in these first attacks, but EOKA began a campaign of assassination mainly aimed at Greek members of the police force and those who disagreed with the idea of Enosis. A state of emergency was declared by the island’s governor, Lord Harding, in November 1955 and the The British Government started looking for a political solution. In March 1956, Makarios was exiled to the Seychelles, but the emergency continued.

Similarly, Turkish Cypriots saw themselves as Turks living on an island nearby. Fearing marginalization under a Greek-dominated government, they began to advocate for “Taksim”, meaning division and in context the partition of the island. The Turkish Resistance Organization (TMT) was created to promote the idea of dividing Cyprus into separate Greek and Turkish states. This period saw increased violence and communal clashes, further deepening the divide between the two communities. The decision to create TMT was taken at the highest levels of the Turkish Menderes Government in Ankara. TMT fighters were trained, armed and led by a small group of well-disciplined Turkish officers. During 1957, TMT pressured the Turkish Cypriots into withdrawing from any cooperative ties they had with the Greek Cypriots and, overall, they were successful; this policy later became known as the `from Turk to Turk policy’. The first serious inter-communal fighting began in June 1958.

Long Awaited Independence

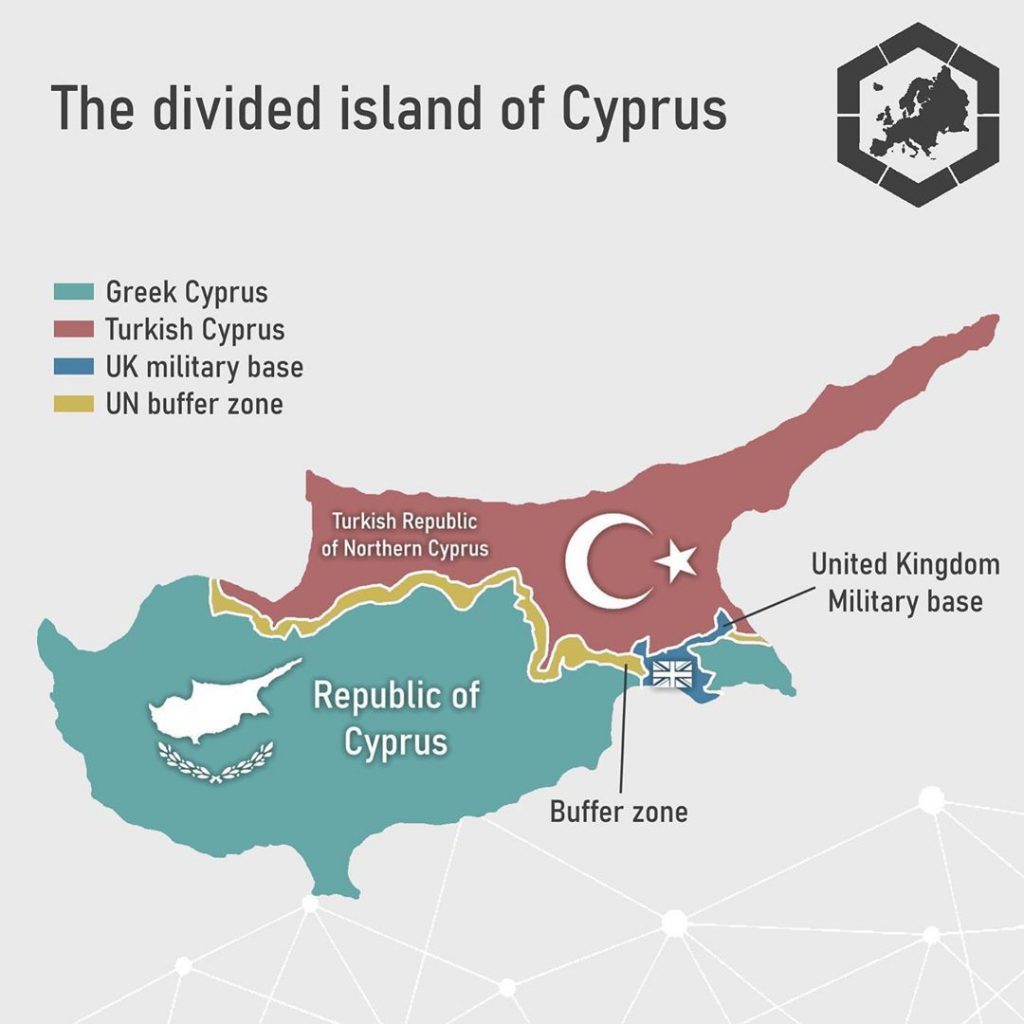

On 19 February 1959 an agreement on independence for Cyprus was reached in Zürich and London between the Cypriot communities, under the leadership of Archbishop Makarios III for the Greek Cypriots and Dr. Fazıl Küçük for the Turkish Cypriots, Turkey, Greece and the UK. And on 16 August 1960 the Republic of Cyprus was founded as an independent state by the Greek Cypriot and Turkish Cypriot communities who share power. On September 20, 1960, Cyprus became a UN member state. The independence only made the desire for self-determination grow. After 3 years, the government collapsed because of a lack of communication and trust between the two communities. On 15 February 1964 the representatives of the United Kingdom and of Cyprus requested urgent action by the Security Council. On the same day, the Secretary-General appealed to all concerned for restraint. He was already engaged in intensive consultations with all the parties about the functions and organization of a United Nations force and recommended the creation of a United Nations Peacekeeping Force in Cyprus (UNFICYP), with the consent of the government of Cyprus. The UNFICYP then intervened and established its headquarters dividing the two communities by a line, called the “Green Line”.

The conflict reached its peak with the coup d’état on July 15, 1974, orchestrated by the Greek military junta and the Cypriot National Guard. The coup aimed to overthrow President Makarios III and achieve Enosis. In response to the coup, Turkey launched a military intervention on July 20, 1974, citing its role as a guarantor power under the Treaty of Guarantee. The Turkish invasion had as its goal to protect the Turkish Cypriot community and restore “constitutional order”. However, the intervention quickly escalated into a full-scale conflict, resulting in significant casualties and displacement of populations. By the end of the conflict, Turkey had gained control of approximately 37% of the island’s territory, leading to the establishment of the self-declared Turkish Republic of Northern Cyprus (TRNC) in 1983. The international community, however, did not recognize the TRNC, and the island remained divided along the Green Line. The events of 1974 had long lasting impacts on Cyprus as thousands of people were displaced, creating a refugee crisis that affected both communities.

Maintaining Peace

Since then, the main instrument for maintaining calm on the island has been and remains the United Nations peacekeeping force, which continues to carry out its task of conflict control. The differences between the communities of Cyprus persist until this day. The south has seen considerable growth, benefiting from EU membership, a thriving tourism sector, and a diversified economy. In the south, there is better access to employment, healthcare, and education, while the north faces difficulties in these areas due to its limited resources, international isolation, and its reliance on financial aid from Turkey. Cultural identities have become more pronounced, and while efforts to foster social integration continue. Efforts toward reunification have been ongoing for decades, for example the opening of border crossings in 2003 has allowed for more frequent interactions between the two communities. Though emotional and psychological barriers remain, and trust between the groups is still fragile. Confidence-building measures, such as joint cultural and sporting events, have also been implemented to reduce tensions and promote dialogue. International support has been a key factor in these efforts, with the European Union and other global actors providing diplomatic banking and financial aid. Recently, there have been renewed attempts to restart reunification talks, though political negotiations continue to face significant obstacles, particularly regarding governance, property rights, and security. Despite these challenges, the persistence of dialogue and cooperation offers hope for a more unified future.

From the island’s ancient colonial history to the strategic interests of imperial powers like the Ottomans and the British, Cyprus’s identity has been shaped by numerous cultures and foreign influences. The events of 1974, culminating in the Turkish invasion and later division of the island, have had a profound impact on both communities, creating lasting social, economic, and psychological divisions. While efforts at reconciliation and reunification have been ongoing, progress has been slow due to the deep-rooted mistrust and the complexity of the issues at stake. Despite the challenges, the persistence of cooperation between the communities through initiatives such as bicommunal committees and cultural exchanges demonstrates that the path to reunification remains a possibility.

Barbara Jhek Kudryk / S6 FRC / EEB1 Uccle